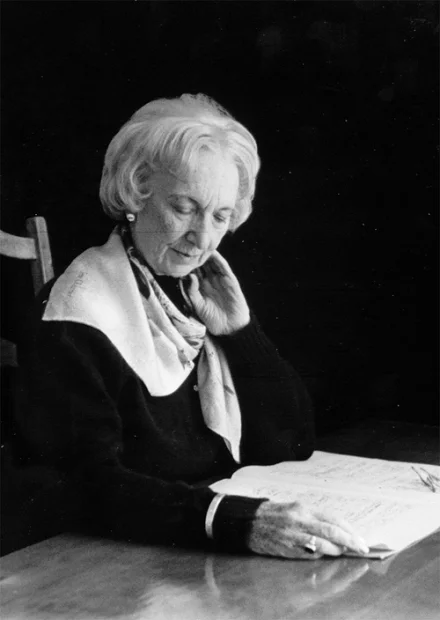

CELEBRATING THE WEST COAST COMPOSERS: JEAN COULTHARD (1908-2000)

By David Gordon Duke (with critical notes by Geoffrey Newman)

The compositions of Vancouver composer and former UBC professor Jean Coulthard rightly achieved strong and widespread appreciation during her lifetime, yet her work seems to be gaining even more reverence now. Just a year ago, BBC Radio 3 added Coulthard to its long-running series Composer of the Week – the first Canadian to be so chosen. In the course of five hour-long programs, music written in every stage of the composer’s long and varied musical development was sampled, and the fundamental story of her life in music told. Her selection may have surprised many, but one influential force perhaps was that the BBC has been actively searching out the work of neglected female composers. Coulthard also did have strong and lasting ties with music in the UK. Nonetheless, one must presume that it was the sheer scope and quality of her compositions that was ultimately persuasive. Here was a 20th century woman from distant British Columbia who wrote in all the great classical genres, a composer who developed a unique (if conservative) voice, and whose best music has stood the test of time and critical scrutiny. This article examines Coulthard’s musical background, the distinctive features of her musical voice, and discusses a number of her works performed at an inspired concert at the Canadian Music Centre in Vancouver in early February 2017.

HISTORICAL BACKGROUND

Jean Coulthard was born in Vancouver in 1908. Her father was a pioneer doctor; her mother, a trained singer and pianist. From a precociously early age, she began composing, and by her teens, her resolve to become a composer was obvious. As Vancouver could not offer her the appropriate professional training, Coulthard spent a year in London where she had lessons with the famous British composer Ralph Vaughan Williams. Though her sojourn at the Royal College of Music was doubtlessly a pivotal point in her development, it still left her with only a few of the technical basics needed for her career. She returned to Vancouver, continued writing, and then sought out what advice she could garner from ‘criticism lessons,’ first with Aaron Copland, then Darius Milhaud and Arnold Schoenberg. Arthur Benjamin, who spent the years of the Second World War in Vancouver, encouraged her to write for orchestra, but it was only after further intense study in New York with Bernard Wagenaar that Coulthard’s long years of apprenticeship were over.

The composer often spoke of how the immediate post-war years were a sort of ‘springtime’ for the arts in Canada. Certainly her concentrated and sustained focus on composition made these productive years for her. But it should be remembered that the compositional focus of this era was very much dominated by progressive styles; Coulthard’s idiom was seemingly out of step. In the mid-1950s she decided to spend a year in France. A short course of lessons with Nadia Boulanger proved less than inspiring, but being re-connected with Europe was artistically nourishing. From this moment on she seemed little troubled by where she fit in the Canadian musical landscape, focusing instead on producing works in virtually every genre of classical music and working at her ‘parallel career’ – teaching at the University of British Columbia.

By the time she faced retirement from UBC in 1973, the tide was turning. A more pluralistic attitude to style emerged; performers were discovering the effective, well-crafted compositions in Coulthard’s extensive catalogue, and the growing interest in the careers of women in music helped redefine her achievement. With advanced age came respect, honours, and a modicum of influence, all of which Coulthard enjoyed. She continued to work with unflagging energy until her mid-eighties. Today, Coulthard’s posthumous reputation continues to grow. Many studies of her work have been written by graduate students. Performers at home and abroad program and record her music. And, now, the BBC feature.

THE MUSIC

The concert at the Canadian Music Centre (BC) on this February 10th was held on a fortuitous date, the composer’s birthday. Asked by the CMC to curate the evening, I grappled with an embarrassment of riches, and decided to work with a core group of performers sympathetic to Coulthard’s music. As such, the program sampled works from the mid-40s to the mid-80s, some favourites (the song cycle Spring Rhapsody and the much loved Bird of Dawning, plus some less well-known works (her Lyric Trio and the Second Piano Sonata).The selection gives a fair, if incomplete picture. Coulthard was reluctant to dwell on her chronological development as a composer, and one sees the point. Coulthard is Coulthard from her virtual opus one, Cradle Song, sketched on a winter evening in the early 1930s, through her Sonata for solo cello, a creation of an octogenarian still committed to creating music for friends.

Coulthard’s preferred way of dealing with her dauntingly large catalogue was in fact to divide it up into two categories: gebrauchsmusik compositions written to delight performers and audiences, and a smaller and more select series of works designed to express something else, often personal. I possibly shouldn’t use the word ‘experimental’ to describe these: it has little place in the composer’s aesthetic, though some works, like The Pines of Emily Carr and The Hymn to Creation, may be seen to have their exploratory dimensions. Though Coulthard was always interested in ideas from serial writing to micro-tonality, aleatory effects and extended techniques, she treated them as new, sometimes exotic, ingredients to be incorporated into her music, not as a focus in and of themselves.

In many respects, Coulthard was all about being a professional composer at a time and in a place in which such an idea was unfamiliar. While some setbacks made her wary of trends and momentary enthusiasms, what mattered most to her was creating works that were both technically well-crafted and inspired, truly revealing a composer secure in her craft and enthralled by the joy of creation. Inspiration wasn’t a trendy word for much of the twentieth century, but it was a lodestar for Coulthard. The composer always loved to receive critical feedback on her works, and in honouring that tradition, I have asked Geoffrey Newman of Vancouver Classical Music to supplement my text with his own critical reactions.

For anyone who has not experienced Coulthard’s work, it is the directness and depth of her feelings that seem to penetrate immediately, avoiding any sense of contrivance and reveling in a fully honest, passionate involvement. Influences are wide: one can perhaps still find vestiges of the rhapsodic insistence of Brahms woven throughout her chamber works and English influences (including Delius and Frank Bridge) are present too, often suggesting strong naturalistic imagery. There is a deeply-felt lyricism in her writing that takes many faces, some joyful, some bittersweet, yet they all seem to yearn for something ‘beyond’. Later works absorb features of the French sensibility of Ravel, Debussy and Fauré, with hints of Scriabin, Prokofiev and Rachmaninoff in the bigger orchestral pieces, but these are all wedded with the composer’s own spirit and individuality. While there are modernist moments, the music is squarely in the ‘neo-romantic’ tradition – hence conservative – but her voice as a composer often goes beyond categorization. GN

SELECTED WORKS

Sonata for Cello and Piano (1946): After what amounted to an unusually extended apprenticeship, Coulthard returned to Vancouver in the mid-1940s following studies in New York. A telling measure of her expanded compositional skills and confident artistic resolve is demonstrated in her trio of Sonatas – for piano, oboe and piano, and cello and piano – all composed in a matter of months around the time she joined the staff of the nascent Music Department at the University of British Columbia. The Cello Sonata has had particular good fortune: it was published by the prestigious British firm of Novello, included in James Briscoe’s Historical Anthology of Music by Women Composers, and has been recorded by a number of artists. It features a conventional three-movement design which demonstrates Coulthard’s mastery of traditional form as well as her own extended (but still tonal) harmonic vocabulary.

One finds a particularly passionate response by the composer to the subject matter, sometimes truculent and rhapsodically propelled, other times toying with a more naturalistic fabric. Motives are not complex as such but they are finely-honed, individual and communicate directly. GN

The Bird of Dawning (1949): In the fall of 1941, writer and broadcaster David Brock re-gifted Wyndam Lewis’ A Christmas Book; an Anthology for Moderns to his sister-in-law; ever on the look-out for poetry that suggested songs or other musical adaptations, Coulthard found a short excerpt from Hamlet in the volume. “Some say, that ever ’gainst that season comes/Wherein our Saviour’s birth is celebrated/This bird of dawning singeth all night long:/And then, they say, no spirit can walk abroad;/The nights are wholesome; then no planets strike/No fairy takes, nor witch hath power to charm,/So hallowed and so gracious is the time.” In its first form, heard on this occasion, The Bird of Dawning was for violin and piano, and dedicated to Coulthard’s grandmother. A decade later, she reworked the material for solo violin, harp, and strings, the much loved version more commonly heard today.

While still in the tradition of earlier 20th century violin compositions, the work captures a lovely spring-like radiance as well as a telling wistfulness and yearning. Its pastoral fabric and rhapsodic, searching qualities perhaps ties it to works like Vaughan Williams’ The Lark Ascending, always maintaining simplicity of utterance while bringing out distinctive tonal synergies. GN

Spring Rhapsody (1958): Song writing was a lifelong activity for Coulthard: she began composing for voice in her teens and continued until her mid-eighties. Written a decade after the Cello Sonata, Spring Rhapsody was a commission from the Vancouver International Festival for the great Canadian contralto Maureen Forrester. Three of the texts are by ‘Confederation poets’ – Victorian writers who were decidedly unfashionable in the middle years of the twentieth century. Coulthard found three evocative poems and added a contemporary lyric by Louis Mackay, creating what amounts to a four-movement ‘song sonata.’ Though she would go on to create many, many other works for piano and voice, Spring Rhapsody was something of a personal favourite and Coulthard invited Forrester to sing the work on her 1978 gala Seventieth Birthday Concert.

There is a wonderful sense of discovery in these four songs, moving from the dramatic and overwhelmingly heartfelt to the beguilingly sensual and lyrical. The lovely final song ‘Ecstacy’ finds some of the light, perfumed colour of Debussy. GN

Lyric Trio (1968): In one of the few important public addresses Coulthard made, she delivered an autobiographical talk about the activity that a generalist composer in our country could (and probably should) engage in. One of the top categories was ‘writing for friends.’ And Coulthard valued none of her musical friends more than the members of the remarkable Rolston family. The Lyric Trio celebrates Tom and Isobel Rolston, who performed so many Coulthard works, and commemorates the birth of their (now famous) daughter Shauna. Coulthard seemed to have no doubts that Shauna would be a cellist and that she would in time join her parents in music making. The Lyric Trio was finished in the summer months the year after Shauna’s birth, written more or less at the same time as The Pines of Emily Carr.

The composition has an underlying warmth, seeking tenderness and wonder in the opening movement and, later, finding a French insouciance and a structural density akin to Fauré and Ravel. It is of some intrigue that the composer revisits English neoclassical form in the finale but still sustains the emotional richness of, say, the Piano Quintet of Cesar Franck. This is a particularly fine work. GN

Second Piano Sonata (1986): Together with the two Images and the last Preludes, the Second Piano Sonata is one of Coulthard’s ‘late’ piano works, a summing up of her thoughts about keyboard writing. Like the First Sonata composed four decades earlier, it affirms her belief in the lasting importance of traditional formal structures and an expanded, tonal harmony. The middle movement is given the familiar subtitle ‘Threnody’ – a favourite Coulthard description for music of sombre, philosophic, and even mournful character. The outer sections, on the other hand, bristle with energy and demonstrate her original, and practical, understanding of keyboard figuration and colour. The Sonata is dedicated to Jane Coop, who premiered the work in Washington D.C. in 1989.

This is a more complex and difficult piece, maintaining a structural tenacity and a direct emotional focus, but taking on more modern novelties and juxtapositions. Coulthard again finds Debussy-like countenances throughout, not least in the striking second movement, and fuses combustible energy with moments of ethereal luminescence later on. Occasionally there is a hint of both the stark angularity and the impulsive freedom of composers like Janacek. Some parts may not have the natural fluency of the earlier works, and involve a more labourious assembling of parts, but one is never in doubt of the conquest being undertaken. GN

Perhaps the real motto of Coulthard’s single-minded quest to be British Columbia’s first composer of international stature can be found in the final words in ‘Ecstacy’ in Spring Rhapsody. In it, the poet D.C. Scott implicitly compares the artist’s raison d’être to the song of the skylark: “Heard or unheard in the night, in the light: Sing there! Sing there!”

There are far worse ways of viewing a life in music.

SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY

Bruneau, William and David Gordon Duke, Jean Coulthard: a Life in Music, Ronsdale Press, Vancouver, 2005

Kydd, Roseanne. "Jean Coulthard: A Revised View." SoundNotes. SN2:14-24, 1992.

SELECTED RECORDINGS

Canadian Composer Portraits: Jean Coulthard, Centrediscs, 2002 (2 disc set)

Ovation, Vol. 1, CBC Records, 2002

When Music Sounds (Works for cello and piano by Coulthard, etc), Naxos Canadian Classics, 2014

Where the Trade Winds Blow on Trade Winds, Tiresias Duo (Mark Takeshi McGregor; Rachel Kiyo Iwaasa) Redshift Records, 2013

Terence Dawson, piano; Sean Bickerton, CMC BC Director; Rachel Iwaasa, piano; David Duke; Joseph Elworthy, cello; Amanda Chan, piano; Nicholas Wright, violin; Robyn Driedger-Klassen, soprano; Stefan Hintersteininger, CMC BC Librarian

Photo: Tom Hudock

© David Gordon Duke and Geoffrey Newman 2017

DAVID GORDON DUKE was born in Vancouver and has degrees in musicology from UBC, the University of North Carolina, and the University of Victoria. He also studied composition privately with Jean Coulthard. He currently teaches at the School of Music, Vancouver Community College and writes about classical music for The Vancouver Sun, The American Record Guide, and Classical Voice North America.